Robert Bellah and his co-authors (1985) coined the term, “community of memory”, which defines an organization’s conscience and holds what an organization deems as good, (as cited in Arnett, Harden Fritz, and Bell, 2009, p. 145[1]). Arnett, Harden Fritz, and Bell (2009) [2] go on to say that from a communication ethics perspective, an organization holds the sense of good, giving the individuals a sense of meaning. Minow describes the community of memory as a social group that keeps the past alive by communicating the narrative again and again, (Minow, 2009)[3]. Not only does the retelling of these stories reinforce positive memories, but they can relive painful experiences as well.

Retrieved from http://media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/originals/a3/ad/31/a3ad31b729d05da1ffa6c1748e7765a5.jpg

In my organization we frequently document both best practices and lessons learned after a major effort. The documentation of both of these practices helps reinforce the “community of memory” as the members of the organization can understand key success factors and detriments. The reinforcement of the best practices and lessons learned results in our ability to achieve better and better results over time, with the desired outcome being flawless execution.

One particular example I can provide is the development of a PowerPoint presentation for a high-profile executive. In the past, a team had developed a lengthy presentation with a lot of detail. The team wanted to be prepared to answer any question this executive, whom I’ll call Dot, would possible ask. While I admire the team for trying to proactively address those questions, they did not have a successful presentation with this executive. Dot had many questions on the first slide, which resulted in them not moving beyond slide one in their presentation. They didn’t have a strong executive summary, so their conversation got derailed by discussing tactics that weren’t relevant to the conversation. They didn’t enter the conversation with a clear “ask” of what they needed from the executive, so the executive provided feedback on components that weren’t relevant for moving forward. The end result was that the team did not get any forward movement and they had to reschedule their meeting with Dot, which took months due to her busy schedule, and their project timing was derailed.

We documented lessons learned from this project and we were able to make adjustments to a presentation that had to go in front of Dot the following month. We created a strong executive summary slide, with the knowledge that we may not move beyond that first slide. We cut down on the content and reduced the total slides to two, with supplemental information in the appendix if questions arose. We also had the clear “Call to action” on the first slide so we would be sure to lead with what we needed from Dot to move forward. The result was a successful presentation with the team having the clear next steps for moving forward. These experiences create the “community of memory” as both the positive and negative encounters can form the narrative for how teams need to operate to be successful.

Retrieved from http://demilica24.tumblr.com

Arnett, Harden Fritz, and Bell (2009) state, “Rhetorical interruption is the disruptive factor, calling our sense of home into question. A rhetorical interruption is simply a communicative event that disrupts our sense of the routine,” (p. 164[4]). We certainly saw a rhetorical interruption in our organization when we merged with another company. The “best practices” that we developed in our company didn’t necessarily work well in the company in which we merged. That company had their own set of “best practices” and “lessons learned” and ours didn’t always match up. This was especially true when it came to intercultural communication. The company in which we merged was a truly global company, with locations in Europe, Latin America, Africa and Asia Pacific. This served as a “rhetorical interruption” because the company now had to think and act globally. Acting globally required a new set of best practices, from the time in which meetings were scheduled to how to engage with the executives to communicating to employees. We had to forgo some of the “community of memory” that had served us before.

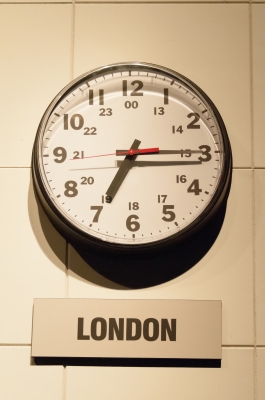

One specific example was the “community of memory” formed around planning team all hands meetings. These meetings were typically held quarterly and all employees in the organization were invited to attend. Previously the meetings were held at 11:00 a.m. EST, making the meeting at 11:00 p.m. in Hong Kong, 8:00 a.m. in California, 12:00 (noon) in Brazil, 4:00 p.m. in London and 8:30 p.m. in New Delhi, India (“TimeandDate”, n.d.)[5].

It’s difficult to find one time to accommodate all time zones, but it was not ethically responsible to only offer a time that worked for U.S. partners on an ongoing basis without considering the needs of our Asia Pacific partners. This “rhetorical interruption” caused us to develop a new best practice, which was to conduct two All Hands meetings each quarter. One meeting would be held at 11:00 a.m. for U.S., Latin America and Europe employees. We would hold a second meeting at 8:00 p.m. EST so that our employees in Hong Kong (8:00 a.m.) and India (5:30 p.m.) could attend as part of their normal business day.

Modifying the meeting times was just one way that the organization could implement a ethical communication behavior that would mitigate the rhetorical interruption.

Have you had experience working with a global company? Did you make any communication adjustments to ensure the organization was acting ethically to all employees?

[1]Arnett, B.C., Harden Fritz, J.M.& Bell, L.M. (2009). Communication ethics Literacy: Dialogue and Difference. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

[2]Arnett, B.C., Harden Fritz, J.M.& Bell, L.M. (2009). Communication ethics Literacy: Dialogue and Difference. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

[3] Minow, M. (2002). Breaking the Cycles of Hatred: Memory, Law and Repair. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

[4]Arnett, B.C., Harden Fritz, J.M.& Bell, L.M. (2009). Communication ethics Literacy: Dialogue and Difference. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

[5] Timeanddate.com. (n.d.). Time Zone Converter – Time Difference Calculator. Retrieved from http://www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/converter.html.